My friend and fellow base jumper Philipp Halla from Vertical BASE Team achieved an awesome jump on the South American continent in February 2012. Visiting Sierra Nevada del Cocuy with the goal of opening a new exit point: “vertical 1” as he jumped the 600 meter vertical east wall of the 5.100 meter high Pan de Azucar.

The 6-member team including the two Colombian guides Felipe Acosta and Darwin Brawo, the Tyrolean climber Christoph Gruber, the Mexican mountaineer Moises Hernandez and the Slovenian allrounder Ziga Legvart have set up in the Sierra Nevada del Cocuy a new record. For the first time an Austrian BASE jumper managed a BASE jump over 5,000 m from sealevel. In comparison, the highest European mountain, the Mont Blanc, has just 4.807m and there is no way to jump without a wingsuit.

With good backing from Volkswagen Colombia, kindly sponsoring 2 team cars that easily would handle the teams back country adventures they set off to prepare this fantastic jump. Originally the plan was to also base jump the Toti, a 4950m peak. So in preparation the 4950m was climbed, but because of an ice storm the attempt for the BASE jump was aborted. The decision was then made to aim exclusively for a base jump from the 5.100 meter high Pan de Azucar.

Two days later, one team departed for the summit, and a second team went to prepare and secure the landing area. Anticipating the best weather conditions at sunrise, the summit team with Brawo, Legvart and Halla departed at 02:00 am in the night. Reaching the summit after a long climb the team now stood on top of the 600m high east wall of the 5100m high „Pan de Azucar“.

With good help from the ground crew and a hand full of rock drops, Halla managed to find a near perfect spot for the exit – a 600 meter vertical drop from exit to the talus. Here is Philipps story in his own words:

Vertical BASE climb Expedition Sierra Nevada del Cocuy 2012

Original words by Philipp Halla, edited and translated from german by Anders Lau Nielsen

Moises is clearly the most accurate of our team. He counted and photographed the climbing equipment before our expedition, and now, after our adventure, as we are dividing our equipment amongst us, we realize that one carabiner is missing. Standing beside him, Darwin, our colombian mountain guide knows the answer: One carabiner has been left at the exit point – our newly opened “vertical exit 1“. At first I’m annoyed, but then I must admit that I kind of like the idea that we have left behind our “footprints”. So the next expedition to our exit point will know of our adventure through this single shining metal carabiner.

We gave everything in Sierra Nevada del Cocuy and were richly rewarded.

We made history, we immortalized this vertical wall. Many people will follow our footsteps, but we will forever be the first that ventured there.

But let’s go back to the beginning:

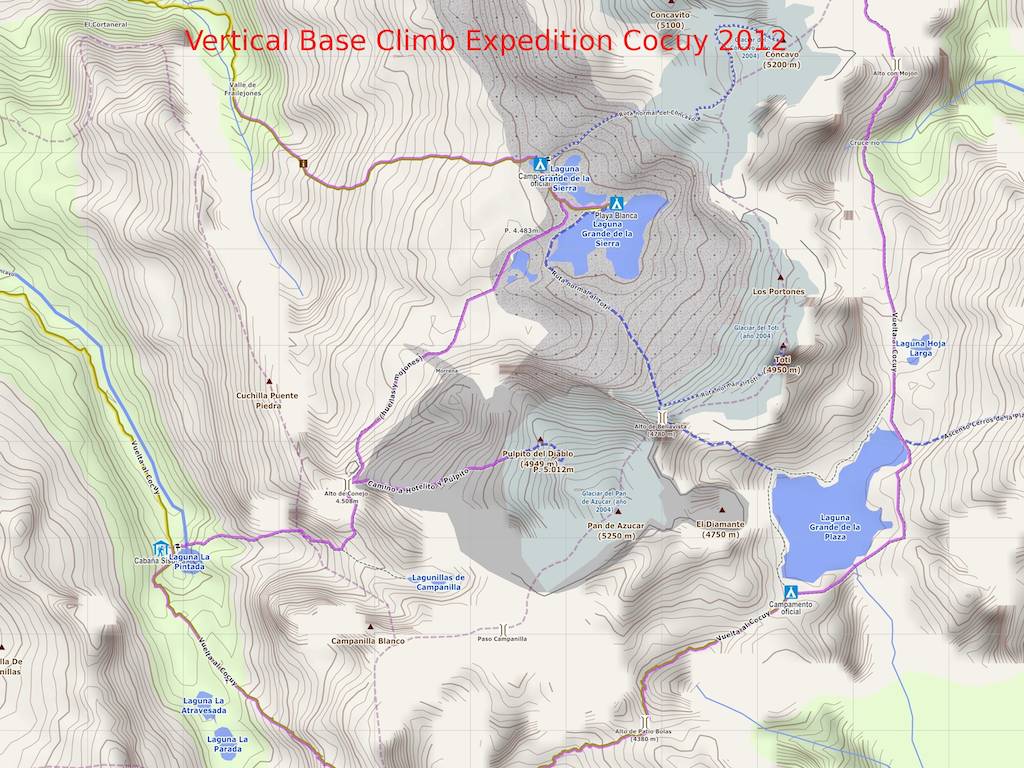

Our expedition goal was the 30 km long Sierra Nevada del Cocuy, one of the most adored mountain regions in the Colombian Andes. For years the mountains were inaccessible, as they were occupied by the Guerillas. In 1986 the french extreme sport adventurer Jean Marc Boivin literally jumped to a world record, when he base jumped from the “Rita Cuba Norte”, 5200 meters above sea level. At the time he became the first human being to ever base jump such a high altitude exit point. His adventure was part of a TV commercial for Dunlop. His ascent was supported by a helicopter. The cliff walls in the Sierra Nevada del Cocuy belong to the highest in the world, and apart from the Karakorum in Pakistan there are only few walls at similar high altitude.

With Google Earth we flew night after night over the various mountains of Sierra Nevada del Cocuy looking for high vertical walls. We stumbled upon the “Pan de Azucar”, 5150m. And next to that the “Toti”, 4950m, which would serve as preparation. I wasn’t especially intimidated by the altitude of the Sierra Nevada, as I had already succeeded climbing mount Elbrus i Kaukasus 5682m and the Stock Kangri 6150m in Himalaya.

But for sure such an expedition still requires a lot of preparation and research. Especially in Colombia information is scarce. By coincidence we discovered the Ort Suesca, a legendary climbing area, close to Bogota. Here the final pieces of the puzzle came together. In this small village, where about 90 % of the Colombian mountain guides and expedition leaders live and train, we sought out competent Cocuy experts. This is how we met Hernan Wilke, who ran a small local mountain wear shop, and who immediately invited us to his family celebration on the occasion of the baptism of his niece. Warmly welcomed by a traditional feast, a buckwheat stuffed pig, and served a dessert of fresh photographs from Hernans latest Cocuy expedition. He actually just returned from the Sierra Nevada del Cocuy where he opened a new line, the “Concarvo”. “Opening a line“ amongst climbers means first ascent of a new route. Through his photos we got a fairly good overview of the area. We were sure there must be some great big walls there.

In the search for a second base jumper we ran into Felipe Acosta, who also lives in Suesca. Via Youtube and Facebook we came in contact with him, and soon after we were invited to one of his

legendary parties. Here we met the guy that did the first ascent of the east wall of the Toti, 4950m. I will never forget his words: “Toti is my peak, Toti is my baby!“. Even though we did not have a large budget for a good paycheck, we were ever so happy that both Darwin Trujilo and Felipe Acosta agreed to be our mountain guides. Also supported by an old climbing friend from Mexico, Moises Hernandez, and a colleague from work, Ziga Legwart from Slovenia, as well as Tyrolean Christoph Gruber who we just happened to run into when polishing our climbing skills. So here we were: a very mixed team of 4 different countries with a common goal: “First ever Base jump from Pan de Azucar!“. Via Facebook we agreed to the schedule and everyone went on training to become well armed for the tour. One should never underestimate the 5000 meter climbing altitude, as there is only about half the air pressure at hand, and oxygen is a rather scarce resource.

The plan was relatively simple: go, climb, jump, go back…but none the less there were several things with regard to the base jump that I needed to contemplate and plan. How would the air pressure affect the canopy ride or the opening? Which angle should I be able to fly to make it back to the safe landing area? And most importantly, how high are the vertical walls really? Everyone I talked to told me different numbers, ranging from 200m to 600m. The real hight would be the key to which packing configuration I would need for the base canopy. For high jumps the canopy must be packed specifically for this and vice versa. After careful considerations I decided to go with a slider-up configuration, which simply means that I would need a minimum of 300m flight, as the canopy needs more speed for best case on-heading and stable opening in this configuration.

Up to the moment of the actual jump we were unsure which was the right size of the pilot chute (PC), the small assist canopy that pulls the main canopy from the container. There is no literature on this subject, how would the high altitude affect the opening? So we considered a larger PC, a 38“ instead of the general 36“. This could result in a bit harder opening, but rather that, than a delayed one.

These essential questions ran through our minds during the expedition and caused some concern, but there are very few people who can actually help answer them. From my opinion there are few people world wide who have experienced such conditions. Felipe’s opinion was: “Take care, you will fall like a rock and the opening will be delayed”. Also he pointed out that the landing speed would be much faster…all these issues did not leave any piece of mind, so to get an additional opinion I wrote an email to Jean Noel from AdrenalinBase.com: “Hello Jean Noel, I am planning to jump in Colombia (Sierra Nevada de Cocuy) from 5000m. I have to cross quite a big “unlandable terrain” and therefore I have to calculate the sinking rate of my parachute. Do you know witch angle (degree) I can approximately fly with my gear (just little wind from front, my weight is 80kg.) Would be great to hear from you”. He replied: “Hi Philipp, the glide ratio of your parachute is around 2.5, so about 22° slope. This will not change with altitude, but with the front wind it will be reduced. Consider also big pilot chute which will affect the glide ratio. have good jump there. Jeannoel Itzstein”

So we bought our selves a ruler and documented the relevant measurements to calculate the necessary glide angle. (finally we knew why we studied math in school :-). However, the result did not please me. The landing area was relatively far away from the exit point, so I would need to deploy my canopy after only 50-100 meters, to be able to make it to the landing area. A high opening means less separation from the wall, so in case of an off-heading opening or line twists, there would be little or no time to recover safely. You then impact the wall, which often leads to death or injuries. In case of an emergency, the fact that there is no rescue helicopter within 500 km, was another thing that left me rather concerned. If anything should happen, it would take almost 3 days to reach the valley for help. To myself I hoped that we would find a landing area much closer to the exit, so that I could do a longer free fall and have a comfortable separation form the wall.

The adventure begins – travelling to Sierra Nevada del Cocuy

The day of reckoning drew closer and closer. Moises arrived from Mexico City and we gathered with Christoph and Darwin at Ziga’s place. Again, we summarized and tested our food supplies and equipment, made a farewell team photo and then we departed on our new adventure. The plan was to drive through the night. In Suesca we picked up our base jump pro Felipe Acosta and made our way direction north.

I still couldn’t believe we would need 10 hours for the 400 km journey. The Autopiste Norte was super modern and with our 2.0 TSI Volkswagen Tiguan we easily averaged 120 km/h. But after 50 km we had or first puncture, so we continued with our spare tire. The closer we came to the Sierra Nevada, the rougher the roads became. We needed 3 hours for the last 80 km, as our average now was walking pace.

The roads are in rough condition so we got to highly appreciate the 4×4 capabilities of our sponsor cars. We fought through the night and were rewarded with a wonderful sunrise. By now we were already way into the mountains of Sierra Nevada del Cocuy, and with the rising sun, the mountain peaks rose as high silhouettes around us.

In Cocuy, the last village before the trails begin, we bought the remaining supplies, primarily rice and pasta. We purchased our tickets for the National Park, and at the city square we enjoyed the miniature model of the mountain region. Then, a final good full meal, and we were off to Cabana del Herrera located at 3900 meters. This is where we left our two VW Tiguan expedition vehicles. The next day, with help from two pack horses, we made our way with our 200 kg equipment to Laguna de la Plaza. Welcomed by heavy rain we hiked over 3 mountain passes, so after building our tent camp we rushed into our sleeping bags to wait for better conditions, which eventually came the next day.

Waking up, everything is cold and moist, light headaches from the altitude were compensated for by the first rays of sun light. By now we could truly enjoy the magnificence of the Laguna, and before us the majestic vertical walls of the mountains. Felipe prepared a traditional tee, in which a special ingredient was added. A kind of sugar which should bring lots of power to you. The plan for the day was to explore the landing area. At first we hiked towards Pan de Azucar, across the Concarvo. Orientation is pretty difficult, as there are no signed trails and the mountains on and off get covered in fog and clouds.

Our mountain guide Darwin was once lost for 5 hours in these boulder fields. Luckily I had my GPS with me, so I mapped the exact path. We would now easily find the same route back. After 3-4 hours in the boulder field the weather became more and more unpleasant. High wind and rain soaked all of us. Suddenly the sky cleared and before us a 600 meter high wall arose. Directly underneath, by a small ledge, we found and abandoned bivouac with candles and empty water containers. So here climbers have begun their ascent of the wall on earlier expeditions. Next task was to explore the area for a well suited landing area. During our planning we did not recognize that there was an additional ledge, which rose 150 m above the glacier moraine, and it would be very difficult to fly across here under canopy. Luckily, to our great satisfaction, we discovered a brown spot which looked even and flat, just by the mouth of the moraine system. After verification is was clear: we had found the “airport landing strip” of Pan de Azucar. Satisfied we made our way back to base camp. Then we went to look for a possible landing area beneath the Toti, and it was quickly discovered that the perfect spot would be a small beach at the bank of the Laguna.

Attempting the jump at the Toti, 4950m

In the evening we fixed our plans for the coming days. A climbing tour on wet walls were not an option. Originally we wanted to climb the two peaks (Toti and Pan de Azucar) via the Bellavista, which connects the Laguna de Sierra and our Laguna de la Plaza. After long discussions with the mountain guides I changed my mind, and we decided to go only for the Toti via the Bellavista, and to attack the Pan de Azucar from the back side via the glacier.

At 5 am in perfect weather conditions we headed off to the Toti. Felipe and Ziga volunteered to secure the landing area at the Laguna beach, and to film and photograph the base jump from there. Personally I was happy about this, because I needed an experienced base jumper to judge the landing conditions. Landing is often the most difficult part of base jumping. Christoph, Darwin, Moises and I gathered our gear and ventured into the vast boulder field. Even though this is not my first mountain, I had never experienced such a tiring ascent. You take 2 steps forward and then you slide down again…the stockpile of loose rock would take no end…and that at almost 5000m asl.

Christoph and Darwin excelled with their unique physical condition….Moises and I tortured ourselves upwards, meter after meter. At the pass we enjoyed the view into the other valley. To the right the summit of the Toti rose, and to the left we could see the steep ice field that led to the Pan de Azucar. Slowly I started to realize why the colombian mountain guides advised against this route.

Unfortunately the weather changed within minutes, followed by an icy storm. In these conditions we could not think of making a base jump, so we waited for a better opportunity between some rocks.

After 1 hour we could proceed, with steigeisen we moved towards the summit. The route became more and more narrow and exposed. In addition to this, the fresh snow caused some difficulties. Over and over I tested different spots at the cliff edges to look for a vertical drop for a jump. But I couldn’t think of a safe base jump in these conditions. The climbing was hard, and I reached my personal limits. At 15:00 hours we reached the summit and enjoyed the fantastic view in all directions. But as earlier mentioned, the wind was very strong and the vertical walls not very high. At the summit we briefly considered whether to look for a possible exit point by abseiling, but we were running out of time. Another 2 hours would mean a descent though the dark night…from a safety point of view we decided for a rapid descent…

The summit was great, and I will never forget the exposed face. But, were we not to complete the first base jump from this mountain? I did not know whether to be sad or happy…

After this 12 hour mountain tour I was so physically and mentally finished that I could barely eat my risotto…I was at the end, and crawled into tent to sleep. Never had I carried my base equipment for that long without getting to use it…

Making the right decisions?

Well rested, the next day we were blessed with sunshine. Felipe, rather disappointed, asked me immediately why I did not jump. Apparently there were 2 perfect

opportunities during yesterday where the condition were good for a jump. He questioned my readiness and focus on this project, but none the less, I knew that I had made the right decision yesterday. I will not jump for any price when the conditions are not right, then rather go back. I am not 18 years old any more, I do not need to prove anything to people around me.

Strategy changes, having the right people around you

Later in the day we had a talk about strategy. We split into 2 teams and began planning how to attack the Pan de Azucar. We learned from our mistakes of the Toti climb, and this time planned the ascent in the night. We would leave at 02:00 am to be ready at 08:00 am with first sunlight.

We would need another day to reach the Gabanas (mountain shelter) at the foot of the western approach. The summit team would be Darwin, Ziga and myself. I wanted Ziga along with me as he is mentally very strong. We know each other form work and he has a very good situational awareness. Between us, Darwin was the most experienced person, and he would lead us safely to the exit point. The other 3 expedition team members we would need at the landing, especially Felipe who would secure a good judgement for the landing conditions. We brought a tent for both the landing area as well as the exit point, in case we would need to sit out bad weather. After landing I would join with the ground crew and go to Cabanas, and meet up there with Darwin and Ziga. All team members agreed and after a final expedition team photo we were ready for an early night. We slept in the Cabanas, which are located at a lower altitude than our base camp. But that night I did not sleep well. Too much went through my head: on the one hand I was looking forward to the next summit day, I felt the base jump was very realistic to perform there…but what if something happens? There is no hospital, no helicopter rescue….I quickly suppressed these negative thoughts…just a few hours more and off we went…

Attacking Pan de Azucar – mixed feelings

A little delayed, ay 02:30 we took off. By chance we had a full moon, so I could switch off my head lamp. Through the valley, to the far end of it, then a long steep hike, where we, contrary to Bellavista, could follow a visible trail. At the ridge of the Pan de Azucar the terrain flattened, so we named the place “Autopista Norte“.

At first sunlight we arrived at the glacier and the panorama was immense. Next to us the rectangular shaped Pulpito del Diablo, and before us the white giant. We could see all the way to the Laguna del Sierra, and way way in the distance the Rita Cuba Blanco, where Felipe Acosta wants to jump later this year. At the glacier we mounted our steigeisen and ropes. Darwin went first, I was last and Ziga

between us. Ziga’s facial expression revealed that at this point he was struggling with the altitude and his steps became slower. We continuously had to pause, but we approached our planned exit point with every step. The exit point was behind the summit.

The ridge was exposed and a cold storm made our ascent difficult. We did not know exactly how to get off the glacier back to the rock, but to our satisfaction we could walk straight from the ice to the rock.

We arrived at the exit point, at the cliff edge, and now my part was required. Since no one ever jumped from this mountain wall I had no initial pointers to draw upon. Where is this wall really vertical, or perhaps even there is an over-hang? I reached for my laser distance meter and started my exit-search with Darwin. We had already prepared our bivouac, just in case. During our ascent we had already spotted a few possible exit points, but these turned out to have little problems all of them, too low or a ledge sticking out. The exit directly next to our bivouac looked good. Threw 3-4 rock drops, and the rocks impacted after 8-9 seconds, but I did not want to splash into ledge like the 4th rock I dropped. I started to become very worried, got scared! What if I miscalculate this, misjudge things? WHAT EXACTLY AM I DOING HERE?

Epiphany!

Then came a radio call from Christoph: “Philipp, the neighbor cliff looks good from the landing area”. I immediately went over there, and it was clear to me…if it was going to work it would be form here! All rocks dropped fell straight to the talus. The wall was at least 500-600 meters vertical. This would be the exit!

In the mean time, weather conditions changed positively, and the sun broke through. I quickly went to my tent, checked my base jumping gear. After this everything became very hectic, as a weather front was moving in. I agreed on a landing direction with the ground crew. Last radio call from the ground crew: “Philipp, there is no wind!“ After this Darwin hoisted me the final 10 meters to the exit.

Here I stood. No wind, 600 meters vertical wall, landing area in sight…now or never! Just a last gear check, leg straps, chest strap…then another 2 rock drops…

Three….two…one…exit!

I fly next the wall and I feel good, I am stable and can go straight into my tracking position. Slowly I make distance to the wall, pass a small ledge…beneath me the glacier moraine…but now quickly open the canopy…the pilot chute pulls the main canopy out…the 38“ PC does a great job…and bang I’m under my canopy…quick check…everything good, and I am comfortably high…now I can enjoy…make a 90 degree turn, looking back at the wall, then another 90 degree turn and setting up for landing…Felipe and Christoph are running to me, everyone cheering with joy!

Yessss….We made it!!!

All text, photos and video are copyrighted by Team Vertical and AdventureRocket.com. If used by a third party, please be so kind and link back to this original source – thanks.